Benito Antonio Martinez Ocasio, known professionally as Bad Bunny, was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico. While studying at the University of Puerto Rico, he worked as bagger in a supermarket. He was also gaining popularity as a Latin trap and reggaeton singer on the music platform Sound Cloud, and was signed to a record label. That was three (3) years ago. Last Saturday, April 27, 2019, he performed before a sold-out Madison Square Garden in New York City.

In his music review in the April 30, 2019 edition of The New York Times (“A Pop Recalibrator Is Still Changing It Up,” Bad Bunny’s revue spanned his career. All three years), Jon Caramanica describes the experience thusly:

“EVERY SONG BAD BUNNY performed at Madison Square Garden Saturday night came paired with its own specific, vivid, elaborate graphics. The visuals took over screens that hovered above the arena floor and the cross-shaped stage, which was a huge screen itself, giving the effect that the rapper was swimming in a pool of his own creation, a video-game protagonist sprouting out of pixels and into real life.”

During “Tenemos Que Hablar” [“We Have To Talk”], the jumpy pop-punk song from his debut studio album, “X 100 PRE,” the screens were filled with logos of rock bands of varying punkness: the Ramones, Husker Du, Blink-182, Linkin Park and many more. It was as a statement about building bridges, but also audacious flag-planting: Those bands could belong to anyone who ever played a Warped Tour, sure, but they also form part of the DNA of one of the most vital and unusual global pop idols of the now, a Puerto Rican rapper-singer with an uncanny knack for melody and an extravagantly colorful style.

Which is to say, punk is an attitude, and Bad Bunny has it in spades. This sold-out show was an ecstatic and relentless career-spanning revue, made even more impressive by the fact that his recording career is just three years old.

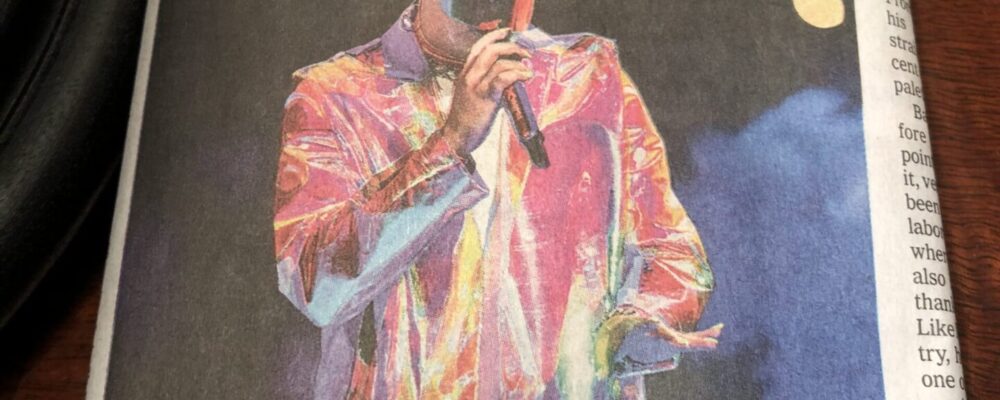

Bad Bunny emerged in a reflective lavender trench coat, his hair the color of a Penn tennis ball, with pointy fingernails to match. From the beginning of his set, he mixed in his early songs — which were more straightforward Latin trap — with more recent ones, which draw on a broader musical palette.

Bad Bunny released “X 100PRE” just before Christmas, putting an exclamation point at the end of a year that, even without it, very much belonged to him. He’d already been one of the most versatile and busy collaborators in the increasingly fluid space where Latin trap flirts with reggaeton, and also Latin pop, bachata and hip hop. And thanks to his appearance on Cardi B’s “I Like It,” for a time the No. 1 song in the country, he leapfrogged his way into becoming one of the most recognizable voices in pop music.

Bad Bunny in The NY Times

At this show, he pivoted among his many styles: brawny rapping on “Caro,” conversational calm on “Otra Noche en Miami” [“Another Night in Miami”], swinging melody on “Diles” [“Tell Them”], his first single, released in 2016. Sometimes, on record, Bad Bunny’s singing seems like a byproduct of his rapping. But on stage, on songs like “Solo de Mi” [“Only Mine”], he was comfortable leaning into the full tenderness of his voice. And in the context of this performance, it was also clear how direct, and almost cloying, his Drake collaboration “Mia” [“Mine”] is — a song designed for smooth absorption that never pushes the edges of Bad Bunny’s gifts.

Midway through the show, he was joined by the Puerto Rican reggaeton star Arcangel for a couple of songs, including “Tu No Vive Así” [“You Don’t Live Like That”]…… The Dominican-American rapper Tali Goya also appeared for one song.

But the more crucial pairing came toward the end of the night, when Bad Bunny was performing “La Romana.” The song starts out as a trap boomer with bachata overtones but shifts gears into something more pulsing and urgent. That’s when El Alfa, the titan of Dominican dembow, shows up. At this show, he ran onstage in a jacket covered in flames made of sequins, rapping in the rat-tat-tat style that he’s been honing since the early 2010s and which he showcased so effectively on last year’s bruiser of an album, “El Hombre.”

Just a couple of years ago, the full ascendance of an artist like Bad Bunny into pop’s mainstream would have been far-fetched. But thanks to his sui generis charisma and style, he’s been instrumental in bringing Latin trap to audiences far beyond the genre’s roots. El Alfa is much more of a forceful literalist than Bad Bunny, and dembow hasn’t travelled as far as Latin trap yet. But when the two men were on stage together, that gap seemed small — the stuff of last year, but maybe not next year.”

In the ever-evolving genres and sub-genres of dance music culture, definitions seem temporary. Trap is a style of hip hop that developed in late 1990s to early 2000s in the South of the U.S. The term “trap” refers to spots where drug deals take place. In 2010s, trap was cross-pollinated with dubstep (a typically instrumental dance music form with sparse, syncopated rhythm and strong baseline), to create trap EDM (Electronic Dance Music intended for dancing in clubs with a customary repetitive beat and a synthesized backing track).

Latin trap or Spanish trap is a style of Latin hip hop that had its origin in Puerto Rico in the early 2010s. It’s a sub-genre of trap influenced by reggaeton and dembow that has spread throughout Latin America. It’s roots are deeply planted in “la calle,” the streets.

Dembow is a musical rhythm that originated in Jamaica. When notable artist Shabba Ranks released “Dem Bow” in 1990, the dembow genre quickly took off. “Riddims” (the Jamaican Patois pronunciation of the English word “rhythm”) were built from the songs and the sound became reminiscent of reggaeton and dancehall music, but with a more constant rhythm and faster than reggaeton. Rhythm and melodies in dembow tend to be simple and repetitive.

Initially, dembow music with its hyper masculinity often heard in the anti-colonial soundscapes of the Caribbean, became homophobic. However, it later faced change and translation, causing it to shed the offensive baggage.

From Jamaica, dembow music reached Panama, New York, and eventually the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico.

Gloria Colon